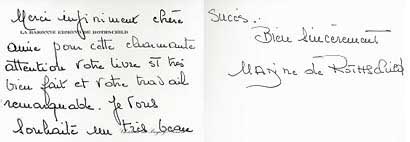

With Baroness Nadine

RESEARCH

I met Edmond de Rothschild when I was writing The little Jewish Pasha of Jerusalem (Crawford House Publishing in Australia has translated it and, the translation being available, is looking for an American and/or British co-publisher). Baron Edmond was a seductive, mysterious man, and was the first to play a key role in the genesis of what would become, after World War II, the State of Israel. His contradictory nature, his “imperialism”, and his prophetic instinct, have given me the desire to explore his life and times. He was first the subject of my thesy for Ph.D, then for a book published in France and translated (by myself) for Crawford House Publishing, Australia – the first biography of a man whose decisive importance has been denied by official historiography, until now.

SUMMARY

Edmond de Rothschild (1845-1934): The Man who redeemed the Holy Land.

Edmond de Rothschild has always been a mystery and an enigma. First, the mystery: why the youngest son of James de Rothschild (1791-1868) - himself the son of the founder of the dynasty - decided, despite the hostility of the rest of his family, to dedicate his energy, time and money to the Jewish settlements in Palestine, from 1882 until his death in 1934?

Why did he decide, at the end of 1924, to create the PICA (Palestine Jewish Colonization Association) and to defend an alternative policy (industrialization, respect of Arabic neighbourhoods, religious education and marriage between Jews) to that of the Zionists?

An enigma, because a certain kind of historiography denied Baron Edmond the primordial role he played in Palestine at least a quarter of a century before the first Zionists, and, after World War I, in the industrialization of Palestine under the British Mandate.

The following are some of my research directions or "trails" for investigation: the ghetto culture; the French laïcité (Edmond de Rothschild became, in 1911, the President of the Consistoire de Paris); the ideas of the Wissenschaft der Judentum, and the Société des Etudes Juives.

But the religious "trail" is the best key to explaining the Baron's motivations. Edmond de Rothschild was very much influenced by his religious teachers, Albert Cohn, and by the great Rabbi Zadoc Kahn, but also by Michel Erlanger and Charles Netter (1828-1882), two of the founders of the Alliance israélite universelle (AIU,1860), the latter being at the forefront (1869) of the foundation of Mikveh-Israël, the school farm (the “messianic farm”) near Jaffa.

When adapting the Balfour Declaration so that the French government could agree to it, Baron Edmond translated the words "National Home" as "le pays des ancêtres" ("The Land of our ancestors") .

The Land of Israel was, by definition, the Mitsva of Baron Edmond (HaNadiv).

.

PRESS BOOK

“Many congratulations on having brought your long task to fruition. First glance tells us that it will be of considerable interest and use to us here.” Victor Gray, Director of The Rothschild Archives.

“Elizabeth, your research is really incredible. I can see that you are a dogged reporter. I also think your ideas and your main thesis is really original and provocative and represents a viewpoint about Rothschild that has not been presented in the other books written about him.

The material that was most compelling was the information you have dug out related to Rothschild and how he is not who you think he is, why he did what he did, and how his nuanced position on so many issues was misunderstood or misinterpreted or overlooked by later Zionist historians who have mainly dominated the narrative of the early years of Palestine. … I see this book as offering a really important revisionist history (the word revisionist has taken on negative connotations but I use it in its original and positive spirit, that it offers a counter-narrative to the one that is most familiar to students of history) about the beginnings of Jewish settlement in Palestine.

I think your book is fascinating and that you offer something that no other Rothschild writer has done before.”

Amy Dockser Marcus, Journalist at the Wall Street Journal, and author of The View from Nebo, Little, Brown and Co., 2000.

“From 1882 on - fifteen years before Theodor Herzl created his Zionist Organization -, Baron Edmond de Rothschild had invested around half-a-million dollars (the budget of a nation) buying lands which traced the invisible frontier of the future State of Israel. In thirty-two years, he had founded around twenty settlements, and had laid the foundations of its future industrialization. In Edmond de Rothschild. L’Homme qui racheta la Terre Sainte (The Man who redeemed the Holy Land), Elizabeth Antébi examines the destiny of this forgotten hero of the official history, that man of faith who, willing to stop the Wandering Jew, suggested once that he never did that in order to create the Wandering Arab.”

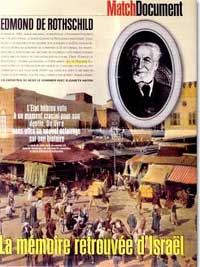

THE HEBREW STATE WILL HAVE ELECTION AT A CRUCIAL TIME FOR ITS DESTINY. A BOOK THROWS NEW LIGHT ON ITS HISTORY.

An interview with Elizabeth Antébi by Régis Sommier:

- How did you discover the character of Edmond de Rothschild ?

- First for personal and family reasons. Ten years ago, I wanted to write the history of my two grandmothers, one, born in Lorraine, having seen the end of the Ottoman Empire, the other, born in Tyrol, having seen the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Looking at old papers, I discovered an portfolio with three extraordinary letters written by my grandfather, Albert Antébi, the husband of my Lorraine grandmother. The family never spoke about this man. In his letters he alluded to a Rothschild who owed him money! I began to investigate this grandfather who wrote a lot about the unknown history of Ottoman Palestine, just before the English Mandate, between the 1870s and 1914. Born in Damascus, speaking Arabic, he belonged to the Jews called Sefarades, but his family never spoke Spanish and never lived in that region around the city now known as Gaziantep from whence they came (see L’Homme du Sérail, 1996). He felt Ottoman, speaking also Hebrew and French, with a little bit of English. He used his Ottoman citizenship to buy land for Baron Rothschild.

- Why could Baron Edmond not buy the land in his own name?

- In 1891, the sultan had enacted very harsh laws, because of the Moslem and Christian Arab sheikhs, to prevent Jews buying properties in the Holy Land. Owing to his Ottoman citizenship and his sense of the Arab, French and Hebrew laws, my grandfather was the perfect go-between for what was then “The Rothschild Colonization”.

- Why is this role in the history of the first settlements not better known in the history of the genesis of Israel?

- It’s known. But it’s a little bit like the tale of Edgar Allan Poe in The Stolen Letter. Any Israeli will tell you that he knows perfectly well the story of Edmond de Rothschild, but he doesn’t know really how decisive was his role. Because Baron Edmond was never politically correct. In the history of Israel – re-written in a Soviet style – Edmond de Rothschild is shown as a nice old man (always old!), like a caricature of a charming millionaire. On the contrary, if you read what he wrote, or what others have said, you can very easily see how young he was all his life long, with an enthusiasm, a vitality, an ability to never be discouraged, to always marvel at the smallest thing … And, as Minister Ben Gurion wrote once, if you trace the link between his settlements, you can see … the current frontiers of the State of Israel. What was really embarrassing for Zionists was the Baron’s idea of a religious Redemption (Gueoulah): for the Baron, indeed, Eretz Israel could only exist as the place where Jewish people could act as guarantor of the morals of the world. Jewish people, for him, was not only elected, it was elected in order to bear witness to the ten Commandments.

- Can one argue that Edmond de Rothschild, banker and capitalist, was not fitting to the ascetic and socialist ideology developed by Theodor Herzl and his Zionist organisation?

- The Zionist organization was not founded before 1897, i.e., fifteen years after Edmond de Rothschild had started his action in Palestine, and the Zionists were not homogenous. Among them, one could meet people of the Right or even extreme-Right wing, and Rothschild liked, for example, somebody like Jabotinsky. The Zionists were, in general, indifferent to his bourgeois side, to his “Queen Marie-Antoinette”-like manners, or his way of being carried in a palanquin. What they disliked was that Edmond de Rothschild had always extolled assimilation to the country, which means a natural and graduated action. He wanted everybody, in the future, to live in harmony together. But the Arab society – and the reverse was true – didn’t understand anything about European Jews from Ukraine, Russia or Germany, arriving with their dreams of equality (between the sheik and the fellah), and constructing barriers in a country of Bedouins, where the idea of private property was totally different. The shock of cultures was also huge. Just before World War I, Zionist women walked outside bare-armed and wearing pants, they smoked and had no veil. For the Arabs of the time (and even for some Jews) it was a scandal. What’s more, Russian bourgeoisie would rather buy hats than cows. And the baron was in total opposition to that kind of behaviour.

- But he wanted Jews to take over the control of Palestinian society, didn’t he?

- He honestly thought that Jews were better economically prepared as Arabs. … But Edmond de Rothschild was opposed to the militant atheism of a big part of the Zionists. He believed deeply in religious transmission inside the family and could not stand that, in a kibbutz, children could have been separated from their parents. Furthermore, at a time when Zionists have used the bric-a-brac of the “New Man” and wanted a life symbolized by farming and agriculture, Rothschild - who had, for years, sponsored the first agricultural settlements and even the experimental farm-school of Mikveh-Israel – used to say that “Capital was the first settler”. After 1920, his goal was to help businessmen in order to industrialize Palestine and … he hated publicity. Moreover, at the time of the construction of Tel-Aviv in 1925, Jewish communists of the extreme-Left wing had forbidden non-Jews to work, and then the non-Unionists workers would come on building sites and participate in roadworks. For Edmond de Rothschild, that kind of sectarism didn’t augur well for the future … The tragedy for the Israeli society of today is that all the people who have always been a bridge between Orient and Occident have been pulled apart. For example, the Ottoman Jews, born and raised with Arabs, speaking Arabic, were ideal go-betweens, the Occidental culture at their core, but also with Oriental “genes”. Edmond de Rothschild died in 1934 and will never know the Shoah. And, precisely, his message is of great importance, because he is delivering us a vision before the advent of Shoah, before any political view, at a time when America begins to be an international diplomatic power – with three Jewish ambassadors in the Ottoman Empire, Strauss, Morgenthau, Elkus.… Indeed, what happens today is worse than the “politically correct”, it’s the “correct memory”, the re-formatting of memory.

[…] The idea of the “redemption” through buying land is at the centre of the action of the Baron. During the Middle Ages, you have to remember there were payments of tithes (Indulgence) to the Church. That idea of money redeeming somebody or something, of an exchange of energy, lies also in psycho-analysis. For the Baron, it’s called gueoula, buying the land and redeeming it for the Jewish people.

- Is not the antagonistic relationship between Edmond de Rothschild and the other supporters of a coming back to the Land of Israel, representative of a secular opposition between a French and universal vision on the one side, and, at the other, a German and Russian authoritarian and military political tradition? Do you think that?

- The Alliance israélite universelle was always the logistic support of Edmond de Rothschild. These schools of thought around the Mediterranean Sea and in the Middle East were, then, the models for the Alliance Française, which means the presence of a very deep French influence in this region, long before the Declaration of Human Rights. That kind of “idealism” is completely opposed, by nature, to the ideology (and the use of that word comes from Germany – it was used for the first time in 1848 by Marx), which has produced, during all the 20th century, the eradication of memory. … In Israel, one “obliterated” the past, of what had happened during the British Mandate, and specially events during the period of Ottoman Palestine, when everything was in the embryo stage. Nobody can ever construct anything without knowing the past. Israeli society has to be involved in the Oriental world as much as in Western politics. Edmond de Rothschild would probably say with me: “We have to stop the massacre of memory”. (Paris-Match, January 30 to February 6, 2003)

TV Programme, Channel 2: “The two Barons”, by Josy Eisenberg. TV Programme, Channel 2: “The two Barons”, by Josy Eisenberg.

“Edmond de Rothschild is born in a nice little mansion, or château, at Boulogne-sur-Seine, a suburb of Paris, on the 19th of August 1845. Son of the founder of the French branch of the family, the baron was, from his childhood, a remarkable collector of art, which he left to the Louvre Museum and which comprised forty thousand engravings, three-thousand-eight-hundred-and-seventy-six drawings, and five-hundred illustrated books. In the excellent biography by Elizabeth Antébi, the author sees, in this “collector’s obsession”, the ‘expression of his daily spiritual research’ and ‘the roots of his future action in Ottoman Palestine’.” Anne Muratori-Philip, Le Figaro Littéraire, May 22, 2003. “Edmond de Rothschild is born in a nice little mansion, or château, at Boulogne-sur-Seine, a suburb of Paris, on the 19th of August 1845. Son of the founder of the French branch of the family, the baron was, from his childhood, a remarkable collector of art, which he left to the Louvre Museum and which comprised forty thousand engravings, three-thousand-eight-hundred-and-seventy-six drawings, and five-hundred illustrated books. In the excellent biography by Elizabeth Antébi, the author sees, in this “collector’s obsession”, the ‘expression of his daily spiritual research’ and ‘the roots of his future action in Ottoman Palestine’.” Anne Muratori-Philip, Le Figaro Littéraire, May 22, 2003.

“Saga, says the author, but also an extraordinary adventure about an epoch without which, probably, the current State of Israel would not be what it is – the basis of this conception was to see Israel as a refuge and a land to be shared. … Rothschild has said in 1934: “The Zionists are always aware of the Wandering Jew, and the risk of creating the Wandering Arab … Idealism alas! But not impossible before World War II, and maybe rich in future possibilities, in a project of peace.” Father Jean-Yves Calvez, s.j., Etudes, April 2003.

“A key book to enable you to understand the historical stakes of war and peace in that part of the world.” Terre Magazine, March 2003.

“In her tenth book, the Zadoc Kahn Prizewinner for the year 2000, Elizabeth Antébi gives us a fascinating biography of an exceptional man, Edmond de Rothschild, who had an extraordinary destiny.” Le Messager, March 2003.

“Everything is not seen through rose-coloured spectacles in this biography and Elizabeth Antébi shows how issues and conflicts still exist there. The five journeys of the Baron in Erez Israel (The Land of Israel) are great moments of emotion, but are also the settling of scores. The Rothschild administration was not liked by everybody, nor, from time to time, by the Baron, nor, from time to time, by the settlers. … Elizabeth Antébi really knows how to tell a story, but she is always remarkably objective.” Ariel Sion, Actualité Juive, Thursday, 27 March 2003.

Zadoc Kahn Prizewinner in the year 2000: here, with M-M Chapuis and the head of the Jewish heritage in France, Max Polonovski :

EXTRACTS

Preface

If you walk a little north, across the port of Haïfa, you will discover a hill, the "Hill of the Benefactor". A gold and black coat of arms - a lion and a unicorn standing on either side of five arrows, with the motto of the five Rothschild brothers, Concordia, Industria, Integritas ("Peace, Work, Integrity") - surmounts the top of the majestic iron gates. As you enter the garden, sweet perfumes are wafted in the air from the most delicate flowers, and then you come to a mausoleum. Here lies Baron Edmond de Rothschild (and his wife, Baroness Adelheid). His life could turn the best scriptwriters in Hollywood green with envy. If you stroll a little bit further, looking at the landscape down to the sea, you can distinguish a low wall, with a map engraved in stone. This map, with lines, notches and Hebrew words, shows the Baron's settlements.

Baron's settlements …

In Israel, nobody talks about them, nobody plans to tour them.

The saga of Baron Edmond de Rothschild is still taught in the schools, buried into the pages of the history books. The settlements have never been destroyed, but survive partly as ghost towns, enclaves, with their painted synagogues, with a platform dividing the former administrators from the plebs, a ritual bath for women behind the stones, a pond for goldfish, the tiles imported from the Mediterranean French port of Marseille stamped with the Napoleon’s bee as a logo, the typical elegant French touch of the ceiling paintings, the plough, some surrealist vision of ladies with feather hats, the room of one of the pioneers with his samovar, some eucalyptus, some tombs, a strange ficus tree, his branches becoming roots for new baobabs …

You can find houses where, scratching below the surfaces of painted walls, you'll discover frescos of rare beauty. They have been partly erased, eroded. Under your hand, colours brighten up. We try to accomplish the work of restoration, of historical renewal, swimming upstream to the genuine sources …

I met the Baron ten years ago, reading letters written in the Ottoman Palestine by my Granddad and send to his superiors of the Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU) based in Paris. This legendary man, called by the press and the local people "The little Jewish Pasha of Jerusalem", was his henchman, his go-between for the purchasing of land; at the time I was writing a book about him. At that time, I read the first letter on the 1914 triumphal visit of the Baron, who disembarked from his yacht Alyah, in Jaffa. Step by step, what I would call the ‘magic of the Baron’, a magnetism felt by everybody who approached him, became palpable. I felt the desire to know a little bit more about this Edmond, son of Baron James, that strange and mysterious Rothschild who, methodically, meticulously, following the Biblical frontiers, delineated his first imaginary map of his Palestine or, better said, what he used to call Eretz-Israël - The Land of Israel. This Land of Israel became a free country, enclosed almost exactly inside the invisible frontiers of yesterday, traced by the Baron.

He was indeed called "The Baron". He didn't want anybody to pronounce his name, partly because he wanted his actions to remain unknown to the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and partly because he was discreet in nature. The settlers and the administration used also to call him HaNadiv Hayadoua (The Well-known Benefactor), the Father of Yishuv (Settlement), HaNassi (The Prince). He was a man on whom no complete biography had ever been written.

Until the year 1970, he was celebrated as a charming old man, very active at a time before events of his life were recorded. His real purpose was overshadowed for reasons that we'll analyze throughout this book. The great historian of the Hibbat Zion (The Love of Zion) 19th century movement, Jean-Marie Delmaire, said: "We had to wait for the studies of Dan Giladi ten years ago to benefit from an impartial and equilibrated study on Rothschild Administration, which has been till now just evocated as a foil to the heroism of the pioneers".

Another enigma is: why did Edmond de Rothschild wait until the age of thirty-seven before committing to this venture of the Holy Land. What was his life like before? Why such a sudden decision?

The more I was investigated, the more puzzled I was by this partial silence and the biased descriptions. The mystery of Edmond de Rothschild remained still intact. In a way, by the time I finished writing this book, even though some of my questions found answers, there still remained a veil of secrecy.

A part of Edmond de Rothschild's mystery is still transgressed.

This old man, ninety years old - we found only one photo of him as a young man - is still fascinating to us, not only because of the historical enigma he embodies, not only for his own paradoxes, but also for the modernity of the problems asked (never solved till now) and of the suggested solutions. Somebody of the AIU, at that time, said once that you must never confuse a nobility title with a title deed. For Edmond de Rothschild, who transferred so many title deeds to settlers and pioneers, the title deeds were bound to a "noble mission" of the entire Jewish people. That mission was the sine qua non condition of the coherence and lasting quality of the revived country, to make "the People", as told in the Bible, able to play his leading moral role, in the world.

How did Edmond de Rothschild spend his time before he reached thirty-seven years of age? As, traditionally, the youngest son of a great Jewish family he was devoted to charities and scarcely became involved in the business of the bank - his eldest brothers, Alphonse and Gustave, assuming that role very well. A daydreamer, sensual and oversensitive by nature, Edmond loved to collect engravings and drawings. Of great integrity, he voluptuously, albeit secretly, abandoned himself to the speculation and contemplation of art. When he wanted to reach a specific target he could whip up his troops, not allowing any contradiction. But he was, in the meantime, able to moderate his first impulse, being both generous and pragmatic.

Do we dare to confess that we procured his astrological portrait? (Serious people can read the next paragraph.) The "amateurs" will be pleased to learn that Edmond de Rothschild was born a Leo, with the rising Sun and Jupiter in Taurus, the Moon in Pisces, Venus and Mercury in Virgo, and Mars, Saturn and Neptune in Aquarius. All that adds up to "a mobile, changing and unpredictable sensitivity, over-oriented to contemplation, a trend to love the marvellous, to be open to the indefinable, and to perceive people and situations as a whole". Somebody, looking at the configuration, concluded: "This character has a tendency to go right to the goal, with no detour, no nuance of any sort. He can move very slowly, but at the end his path is irresistible."

Edmond de Rothschild lived to almost ninety years of age. Born at the rise of the 1848 revolutions throughout Europe, he died at the first simmering of Hitler’s Germany and just before the French "Front Populaire" – an alliance between socialists and communists before World War II.

This character, with his numerous interests and multi-faceted passions, appears like an incredible hero of a novel: a tasteful collector, he bequeathed to the Louvre Museum 40 000 engravings, 3 870 drawings, and 500 illustrated books: his only condition was that they be presented in an aristocatic setting of a "cabinet d'amateur" (special exhibition room). As a member of the French Academy of Fine Arts, he sponsored the digs of archaeologists Clermont-Ganneau in Egypt, Raymond Weyl in Palestine, and Eustache de Lorey in Syria. Together with the Earl of Fels and the Prince of Arenberg, he founded a Comity for French Africa. As a member of the Society of the Friends of Science, he was enthusiastic about the researches of the French physiologist Claude Bernard. Founder in France of the Henri-Poincaré Institute, sponsor of the Institute of Physico-chemical Biology and of the Foundation of the Scientific Research (ancestor of the CNRS), he also gave funds to create the French Institute in London and the Casa Velazquez in Madrid. Not to mention the Palestinian settlements …

In a way, was his collector's emotion in front of a painting like The Synagogue of Albrecht Dürer or an engraving of Rembrandt very different to the feeling of the "well-known benefactor" looking for the first time at the brand new suburb of Tel Aviv, in 1914?

And can we attribute to chance only, his will to buy a substantial collection of rare books and manuscripts on Jewish history and Hebraic literature, which was transferred after his death to the library of the Alliance israélite universelle, in Paris?

In a sort of reverse-hagiographic literature, the role of the Baron was reduced to an (occasional) intervention of an old imperious philanthropic guy, a kind of Queen Marie-Antoinette supplying the most remote towns of the Ottoman Palestine with turkeys, chickens and carrots. In that legendary version, the role of the Jewish natives - Sefarades or Arab-speaking Jews - is completely underestimated, even omitted. Quite the opposite, the Rothschild administration used them not only as informers - to obtain a lot of information about the Palestinian background and way of thinking - but also as intermediaries to intercede with the local authorities on the settlers’ behalf, or as go-betweens to buy, on a very large scale, a large amount of Palestinian lands: not only were these native Jews the most appropriate people to negotiate with the Ottoman Pashas, but also they were the only ones to be authorized to do so because of their Ottoman nationality. We can assume that this intentional rewriting of the history and eclipse of some of the main actors of that time still affects events today in that part of the world.

Until World War I, France worked much towards the "assimilation" of the Jews not only to France, but, as strange at he seems, to Palestine. After the war, Great Britain inherited from the Society of Nations a British mandate on Palestine and, from the years 1920 to 1948 (when the State of Israel was founded ), played its hand with duplicity in order to achieve its own ends.

The presence in Palestine of the Alliance Israélite universelle and of Baron Edmond de Rothschild - i.e., of French and Latin influence - more than thirty years before the first Zionist arriving to work in the Holy Land, was considered, for some ideological reasons, as a "non-historical zone", somewhere in limbo, at the borderline of memory. "Just another philanthropic scheme", wrote the (brilliant) historian of Zionism Walter Laqueur about the Baron's action.

Was not the Baron moved by a prophetic and universal religious sense of the role of the people of Israel? As my research progressed, that question seemed to us more and more accurate. Was not this contradictory and enigmatic religious conception acting as a keystone of his entire action? Remember the name of one of the most famous Rothschild settlements, Rosh-Pinah, referring to Ps. 118, 22: "The stone thrown aside by the builders became the keystone."

Considering it this way, the mission of the People elected to be the witness of the transmission by God to Man of the Ethic of the World lies, till now, concealed, as a stake of civilization.

The word "settlements" doesn't mean, like the French word of "colonization", a military occupation. It would be wrong to think that, at the time when the poor Jews, victims of pogroms, went to Palestine, they had stolen anything belonging to the Arabs. Not only did Baron Edmond bought to the rich Arab families like the Sursock of South Lebanon, insalubrious swampy lands, but also he sponsored very expensive, and for a long time unsuccessful, sinking of wells to find what was indispensable for the daily life of populations - water.

With his great sense of pragmatism, he sponsored also, in each settlement, clinics, schools and synagogues - the sacred triangle of the Rothschild colonization being Health, Education, Religion. In the clinics and in the schools, Arab children were accepted. If, then, conflicts occurred more and more often, it was due much more to oppositions between the behaviours and traditions of the natives of the country and the newcomers: at the time, for example, most of the Jewish women had been veiled. And, of course, the Arabs (specially the Bedouins) did not have the same conception of private property, class struggle or women's liberation as the young Russian socialists.

When Edmond de Rothschild tried, two or three times, to buy the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, he could appear as a weirdo. It was the time when the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire was the Caliph of the Muslim World: he asked the German engineers, Siemens, to construct the railroad for the pilgrimage to Mecca, and it was probably a dream to consider that he could negotiate the buying of the Wall in the third sacred city of Islam. And the unbelievable project almost succeeded. One could not reduce, as was done from time to time, the political and amazing strategic intuition of the Baron as the mere whim of a multi-millionaire.

From the 16th century theological quarrel around the payment of indulgences or, more recently, the rising of the psychoanalysis, we know the symbolic value of money: in the case of Edmond de Rothschild, at the end of the 19th century, when the Holy Land became the spiritual center of the Western world, money could permit the Gueoulah of Eretz-Israël. And the Hebrew word Gueoulah means "redemption", literally buying the land with money, or, spiritually, through good actions, mitsvot. And the supreme mitsvah for the Baron was to work the land of Israel.

From 1882 to 1899, the amount of money spent for the colonization turned around a hundred million dollars - following an estimation by the Harvard economist and historian, David Landes - almost the budget of a State. From where did the money come? A strange question to ask when you talk about the Rothschild family. Most of the Rothschild papers concerning their banking activities were burned or destroyed for reasons of secrecy. But even if the family of Baron Edmond was not favoured towards his Palestinian action, Edmond was close to the decision-makers and aware of the secret currents of diplomacy, especially in the English branch where he was very friendly with his cousin, Natty. And, of course, he had access to the safe.

From a general point of view, one cannot completely trust most of the confidences from people who had met the Baron. This repression of information results in our awareness of his authoritarianism, his liking for secrecy, the power generated by his multi-millionaire status, the mysteries around his motivations - for example when, during the Peace Conference of 1919, he spoke one thing to the Zionist Sokolov, and another to the anti-Zionist Sylvain Lévi, being probably sincere in both cases. But the discomfort of most of the people in front of the Baron could find its source in the strange aura of religion and ethical obsession emanating, partly unwillingly, from the person of Edmond de Rothschild.

The mystery still remains: what did Edmond de Rothschild want to achieve, what was he chasing after? What was the real reason behind his obsessive collecting of the xylographies, the first editions of rare engravings, the copies of some of the world’s earliest books, and the Jewish settlements in Palestine? Is his fondness for possession, as Chaïm Weizmann argued, a key to understanding such an altruistic egoist? Or, can intellectual curiosity explain a passion for scientific discoveries that amazed many scientists and researchers, such as Jean Perrin in France? Was he, with the founding of the French Institute in London or Casa Velazquez in Madrid, a European before the term was ever invented?

The life of Edmond de Rothschild seems to be a little bit erratic if we simply consider the influences on him from persons as diverse as the collector Dr Roth, the scientist Jean Perrin, the great French rabbi of the Dreyfus Case, Zadoc Kahn, or the chemist (and future president of Israel) Chaïm Weizmann. But it could take on another dimension if we just consider his conception of Judaism as putting the accent less on faith than on the acts of faith … to which he subordinated all his life. If we look at every element at the origin of the creation of the Jewish settlements in Palestine, we would have a perfect illustration of the antagonistic interaction between religious and secular fields, or better said "laic" - and, in that particular case, the laos ("lay people" as opposed to "clerical") is the People of Israël … as defined in a religious text, the Bible!

Throughout the 19th century, the study of the Bible and the Talmud entered the laic field. The three European bestsellers of the century, as Professor Henry Laurens professed, are related to Palestine and the history of the Jews: Génie du Christianisme ("Genius of Christianity") of the romantic writer Chateaubriand in 1802, Vie de Jésus ("The Life of Jesus") of the historian of religions Renan in 1863, and the violently anti-Semitic pamphlet La France Juive ("Jewish France") written by the Journalist Drumont in 1886. With the rising sciences of philology, and other new exploration tools, the Bible is submitted to the critiques of experts: the text falls from the status of a religious revelation to the level of a subject able to be submitted to an historical analysis. Laurens calls it the "invention of the Holy Land": "As an answer to texts no more considered as obviously genuine, some of the researchers answer showing ‘witness items’ and pushing to the intensification of archaeological excavations. The Holy Land became the central place of the Occidental thought."

During the second half of the century, a "science of Judaism" was born in Germany and France, and institutions were founded like the Palestine Exploration Fund in London, and the Biblical School in Jerusalem. The archaeological obsession of Baron Edmond de Rothschild was a part of his involvement in rebuilding the Palestine of his ancestors: the mitsvah was to work the earth, upstairs and underneath, to revive Eretz-Israël for the past, present and future.

But if a religious text becomes a historical text, the Bible now just reflects the history of a people like any other history book. Jewish history benefits no more from a status of intangible eternity, it becomes submitted to the contingent time of humanity. Jews discovered that they were actors of history and, then, they wanted to try to modify the script.

Edmond de Rothschild understood immediately the consequences of this new way of considering Jewish history. But Judaism never became for him, as for many other Jews, a religion like another, allied to some positivist or protestant statements. The Jewish people still remained the People of the Law and the people-chosen-to-testify-to-the-Ten-Commandments. He had chosen to act religiously under the land - sponsoring archaeological digs or sinking of wells - and on the land - with the farming, growing and draining in the first stage, to the industrialization and electrification of the country after the World War I.

We will explore this exclusive bind of the Baron to the land as an act of faith and supreme mitsvah ("commandment").

The life and action of Edmond de Rothschild can be sub-divided into three main parts:

1. The youngster "under influence", faithful to the "family mission", submitted to a range of influences - the values of the ghetto, transmitted to him through his father and uncles, fostered by the cousin who became his stepfather; the influence of the Jewish mother who behaved also as a French "coquette", courted by the officer commandant of Paris, praised by the German poet Henrich Heine, portrayed by the painter Ingres, not so young when she gave birth to baby Edmond, the last of her four children; the influence of the cohanim (priests) Albert Cohn and Zadoc Kahn. Edmond de Rothschild was born at the time when the brave old world vanished before the European revolutions of 1848 and when the Rothschildian empire of Austria disappeared. At a time when the French monarchy was shaken, with the emerging of a new class of young Jewish scholars and members of the middle class. This period ended with the terrible conflict of the war of 1870 between French and German armies, and ended in disaster for France when it lost two provinces - Alsace and Lorraine.

2. The politically royalist and democrat man was not involved much in politics. It was the time of the seism of 1905 - the year of the death of the great rabbi Zadoc Kahn and of Alphonse, eldest brother of Edmond and the head of French Judaism for more than half a century. That year was also the birth date of the secularization, i.e., what the French people used to call the Law of Separation (between Church and State), not welcomed enthusiastically by the Jewish gentry because they received grants from the government. Some years after, the Young Turks revolution of 1908-1909 drove the Ottoman Empire also from a government of millets (religious people) to a secular State, taking inspiration from the positivist and even atheist ideas of the time. Edmond de Rothschild was not at all seduced by it and refused to sponsor any newspaper: this lost occasion benefited the Zionists. Edmond de Rothschild has always been a nostalgic of the "ancient order" of the Empires and aggregates of religious peoples, where Jews could play an autonomous role: they had only to be emancipated and to help Zion's revival, following the tendency of "Lovers of Zion": the idea of Love was very essential for Baron Edmond.

3. The man of Eretz ("the Land"), less than of Israel (or because of Israel, as he said once to the Zionist Ussiskin), full of mystery with his geopolitical vision, his detour through archaeology, his attempt to buy the Wailing Wall. And then, his action at the heart of the Jewish Colonization Association, his manipulation of the AIU logistic (1899-1920) for the benefit of his own designs, the great turning point, after twenty years, to buy more and more land - unless to help the existing settlements - and his will to industrialize Palestine to manage the future. After the testimony of 1925, the events of the last nine years of the life of Baron Edmond (1925-1934) seem to us more and more enigmatic: why this indulgence for the founder of the Jewish Legion, the very nationalist Vladimir Jabotinsky, in 1931, at the Exposition Coloniale in Paris? Why this worry about the attitude of the Jewish immigrants facing Arabs and this distrust of the administration of the British mandate? Why did the Baron lean more and more towards the socialist Leon Blum? It was not always easy to find simple answers.

From World War I on, under the pressure of three factors, there happened what we could call an "historiographical hijacking". The three factors were a) the triumph of the German-Russian influence in Jewish Palestine under the British mandate, b) the new order of the world, generated by the Wilson Declaration of 1919, inspired by Justice Brandeis and promulgating the right of peoples to self-determination, c) the rewriting (for ideological reasons) of the history of the pioneers, after the Shoah and the foundation of the State of Israel (1948).

To explore the role of historiography - i.e., the way history is written and transmitted by official historians and affects our collective memory - could be an interesting study. It's not our subject, unless when this historiographical distortion becomes an integral part of the story and hidden non-conformist motivations. The history of the Jewish settlements in Palestine, at least during the first thirty years (from 1869), is closely related to the action of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, directed in Paris by Salomon Goldschmidt and Narcisse Leven, of the Jewish Colonization Association founded in London by Baron de Hirsch, and of Baron Edmond de Rothschild.

The turnaround of ways to consider the claims in that part of the world, began with the takeover of influence by the Zionists (at the time of the Young-Turk revolution of 1909), helped either by Germans wanting to preserve their economic interests in a spirit of Drang nach Osten ("Rise to the East"), or by Russians, willing - as they tried during the eleven former wars against Turkey - to obtain an access to the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus.

Furthermore, the relative silence of the Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs concerning Edmond de Rothschild (very active, as we will see, at the time of the Balfour Declaration of 1917), is significant: "France needs her Muslims troops", remembers Georges Wormser - what the politicians called later the "Arab politics of France", the latter having to preserve her connections with Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. Franklin Bouillon, President of the Foreign Affairs Department of the French Congress, as early as 1926, answered to the Palestinian journalist Ben Avi, for the Dohar Hayom: "France, being a Muslim power with her twenty million Muslim subjects in Africa and Asia, French people cannot support a movement, the purpose of which is not clear and the targets not ours. For that reason, I am now against Zionism."

After World War I, the cards were dealt again with the rules of the game and partners changed completely, geopolitical shifts occurred, and, what is rarely evocated, the big factor of the new era was the eclipse of religion. Religion was even, in many countries, disparaged or fought against.

To the imperialist legitimacy - within which the authoritarianism "inherited directly from god" exerted by Baron Edmond de Rothschild on his settlements founded an appropriate frame - was substituted another legitimacy, of the right of peoples to self-determination. And this new legitimacy has conducted, after World War II, to a redefinition of human rights by the French lawyer René Cassin, new president of the AIU, with, among the signatories … Joseph Stalin of the USSR, marking the changeover, on the world scene, from the subtle games between four or five big powers to the post-war confrontation between two, United States and the Soviet bloc.

Edmond de Rothschild thought that this new order of the world, and the right of peoples to self-determination, could lead to new disorders, with a new question: which peoples? He decided then to ensure the economic independency of Palestine, and said: "Capital is the first settler."

He always chose his suits in England and loved the country, but he didn't always trust English people, with their promises to Zionists, their concessions to Arabs, their way to add fuel to the flames, while he was always willing to calm things down. In 1925, he held the foundation of the Hebraic university of Jerusalem quite aloof, but the "incidents" in front of the Wailing Wall and the slaughters of 1929, and then the call from the Great Mufti of Jerusalem (23rd of September 1929), convinced him to adhere to the Jewish Agency and to seek a rapprochement with … the Second International. At the same time, he disowned young Jews who put the Zionist blue and white flag at the top of Omar mosque. The supporters of the opposite factions had all been disappointed.

What's more, the slaughtered Jews of 1929 could find an asylum inside Rothschild settlements, where no Arab went (because of the good relationships between farmers, sheikhs and fellahs). And, in a letter to the Society of Nations, in 1934, the Baron specified that such a struggle, to put an end to the Wandering Jew, could not have as its result, the creation of the Wandering Arab.

In a world more and more overcome by ideological hemiplegia, it's perhaps normal to think that we have had to wait such a long time before being able to tell the amazing story of this free-thinking renaissance man, so true to his faith and what he believed in.

Dès la Première Guerre mondiale, en effet, un "détournement historiographique" a commencé à s'opérer, sous l'impulsion de l'école anglo-saxonne, relayée par la volonté de réécriture de l'histoire qui s'opère dès la fondation de l'Etat d'Israël (1948) et au lendemain de la Shoah. Le rôle de l'historiographie, c'est-à-dire de la manière dont l'histoire est écrite et transmise par les historiens et affecte, un temps plus ou moins long, la mémoire collective, reste à étudier en détail. Ce n'est pas notre sujet (bien qu’il soit sans doute, de façon latente, au cœur des débats sur nos siècles occidentaux depuis les Lumières) et nous ne l'abordons, au cours de notre enquête, que lorsque la déformation historiographique finit par faire partie intégrante de l'histoire, dans la manière même dont elle l'altère, interposant une "grille" idéologique qui interdit tout accès à un sens plus religieux, plus complexe, à une parole plus dérangeante. L'histoire des colonies juives de Palestine s'identifie en effet, pendant trente ans au moins, avec l'action de l'Alliance israélite universelle, de la Jewish Colonization Association

Car on l'appelait le Baron, il ne voulait pas qu'on prononçât son nom. On le nommait aussi HaNadiv Hayadoua (le Bienfaiteur Bien Connu), le Père du Yishouv, HaNassi (Le Prince). Un homme dont il n'existe nulle part une biographie complète. Un homme auquel on a tout juste commencé à rendre justice dans les années 1970, comme le signale un professeur de l'université de Lille, Jean-Marie Delmaire, qui nous a laissé l'une des thèses les plus complètes, les plus profondes et les plus bouleversantes sur cette époque, De Hibbat Zion [l'Amour de Sion] au sionisme politique

|